![]()

Something that really frustrates me is the way psychology can be seen as ‘woolly’ or ‘soft’ simply because the constructs being studied can’t be touched or visualised. So although I don’t think that neuroimaging represents ‘psychological’ constructs in any sort of a one-to-one sense, it is nice to be able to point to research that provides an underlying biological explanation for some of the abstract concepts that are commonly used to explain psychological aspects of the experience of pain.

While physics, mathematics and allied sciences have developed a technology to measure and quantify physical substances, it’s psychology we have to thank for the generation of measurement strategies for abstract concepts. Incidentally, for a nice user-friendly version of the development of measurement in psychology, this page written by Sally Khulenschmidt is well worth a read.

Anyway, today’s post is about a topical review written by Valery Legrain, Stefaan Van Damme, Chris Eccleston, Karen Davis, David Seminowicz and Geert Crombez examining the behavioural and neuroimaging evidence for a neurocognitive model of attention to pain.

It’s well known now that not all tissue damage is immediately perceived by the brain as ‘pain’, and that in fact a whole chain of events need to occur before we become aware of the fact that our body may be in danger. The relationship between activation of ‘nociceptors’ and the pain experience is influenced by a whole raft of affective and cognitive factors (eg Tracey & Mantyh, 2007, in which different ‘neurosignatures’ are evoked depending on mood and beliefs despite the same nociceptive input).

Attention, or the process by which a person focuses on one feature of a situation while focusing less on others, plays an important role in how much or how little of a stimulus is perceived. A major model used to describe the role of attention suggests that ‘there is limited capacity for information to be attended to, proposing that sensory signals – including nociceptive ones – exceed processing capacity, and hence require attention to select the signals needed for goal-directed behaviors’ (LeGraine, Van Damme et al., 2009) This is suggested to reduce pain (ie be analgesic) by directing attention away from nociceptive information, so that such information is not processed further and is therefore not perceived as ‘pain’.

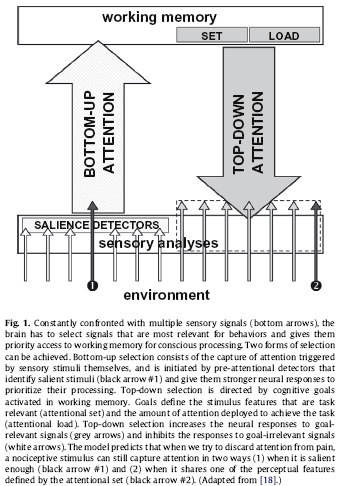

This paper adds to the model I’ve just described by suggesting that there are two mechanisms that help us decide what to attend to and what not – top down, or ‘an intentional and goal-directed process that prioritizes information relevant for current actions’, and bottom up, or ‘unintentional stimulus-driven capture of attention by events themselves … often imposed by the most salient stimuli in our environment, independent of intentional control.‘ (LeGraine, VanDamme et al., 2009).

Salience is about how ‘unique’ or ‘different’ or ‘distinct’ a stimulus is – perhaps it occurs very seldom, or it’s completely different from anything else, or maybe it’s the amount or degree of difference between this stimulus and ‘the norm’ that is unique.

The effect of a new or very different stimulus is to interrupt concentration (have you ever tried to read a book when a kid is wandering about blowing on a recorder? or banging on a drum or going ‘peeow, peeow’!!). But the amount of distraction depends on the goal – if the goal has a lot riding on it, and demands a lot of attention to do it well then it’s going to require a really distracting stimulus to drag your attention from it (ever tried getting a bloke to talk to you during a rugby match? For North American readers, read ‘football’ match?!). Distraction is much more likely to occur if the stimulus is similar to something the person is concentrating on (for example, if you shout ‘Goal’ during a match!).

When we’re discussing pain, it seems that ‘attention is unintentionally captured by pain when it is intense, novel and threatening’ (Ecclestone & Crombez, 1999). This has been studied using neuro-imaging where it has been shown that ‘attentional capture by pain is mediated by the brain areas underlying the P2 responses of laser-evoked potentials’ (Legrain, Damme, Tracey, & Mantyh, 2008). A specific centre, the midcingulate cortex (MCC) is one of the main generators of nociceptive evoked P2, and is activated by new and interesting information, and especially in areas requiring alteration in behaviour in order to achieve a goal. The authors point out that ‘one may think of the MCC as a structure necessary to prompt urgent motor reaction.’

Bottom up attention to pain can be changed or modulated by top-down or goal-oriented activities. There are many examples of this – ever noticed how you acquire bruises during the weekend’s activities, and only notice them on Monday morning?

‘EEG studies show that the amplitude of the P2 component of nociceptive evoked potentials is decreased when participants are performing a more demanding visual task (attentional load hypothesis)’ The authors suggest that ‘top-down attention affects the processing of nociceptive stimuli at early levels by biasing somatosensory brain activity’ – this can work both ways…it can reduce our attention to pain – as my example above illustrates – but it can also increase the attention that gets paid to parts of the body where pain is expected to be experienced (watch what happens when a kid is given an injection to the arm – they’ll be very aware of any little tickle or touch on the arm for quite a while afterwards!). This is supported by ‘findings that pain catastrophizing is associated with greater activity in operculo-insular and MCC areas’.

Prefrontal and parietal areas appear to be involved in ‘top down’ processing of attention toward pain – the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex is involved in maintaining goal-relevant priorities, apparently by directing executive functions toward the processing of task-relevant information in order to avoid interference by goal-irrelevant information. The authors of this paper suggest that ‘the DLPFC and the IPS may help to maintain respectively attentional load and attentional set, to prevent attentional capture and interference by painful stimuli.’

The final conclusions of the authors in this paper suggest that ‘bottom-up’ attention processing may give an attentional bias to salient events that are then held by operculo-insular areas, and by the MCC that triggers an attentional bias to nociceptive signals.’

Top-down modulators act through both attentional load and attentional set. That is, it influences the amount of effort a person invests into monitoring information relevant to goals, supported by the DLPFC that assigns executive functions to the primary task. Then it determines the stimulus that are task-relevant or irrelevant – attending to anything that is deemed to ‘fit’ with the features that are within this ‘attentional set’ – some of which are not relevant at all to the goal being focused upon. The attentional set depends on specific personal goals, balanced with the general goals of maintaining homeostasis.

The implications of this model are many.

Firstly, models like this help develop hypotheses about the differences between experimental pain (acute pain in well-controlled environments) and pain in natural settings (often chronic pain in complex and uncontrolled environments).

Many of the current explanations about loss of cognitive abilities in people with chronic pain are explained by ‘hypervigilance’ to pain, or anxiety, or even depression and/or lack of sleep. If, however, a model like this is used, it could be that patients cannot exert ‘executive control’ over what input they attend to, so that irrelevant stimuli, such as nociceptive input, are attended to over goal-directed input.

Or, perhaps a broader-than-necessary attentional set means that certain information is processed and deemed relevant when it is actually irrelevant. The authors suggest that this may be related to the ongoing search for pain relief – which may be directed less by patients and more by doctors.

The final point these authors make is ‘attention management may be a more important component of cognitive behavioral rehabilitation than traditionally considered’ – and perhaps in different ways too. Not simply being able to direct attention to and from sensations, but also around developing and structuring goals in life.

Food for thought? I wrote about attention management just a short time ago – it works! Take a look here for that post.

LeGraine, V., Van Damme, S., Eccleston, C., Davis, K., Seminowicz, D., & Crombez, G. (2009). A neurocognitive model of attention to pain: Behavioral and neuroimaging evidence Pain DOI: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.03.020

Eccleston C, Crombez G. Pain demands attention: a cognitive-affective model

of the interruptive function of pain. Psychol Bull 1999;125:356–66.

Legrain, V., Damme, S., Tracey I, Mantyh PW. The cerebral signature for pain perception and its

modulation. Neuron 2007;55:377–91Legrain V. La modulation de la douleur par l’attention. Les apports de la

neurophysiologie. The modulation of pain by attention. Insights arising from

neurophysiological studies. Doul Analg 2008;21:99–107.

Its good to see some of the neuroscience of attention being applied to pain. I heard that there is some suggestion that mindfulness practice, which is a particular type of attentional training, tends to develop the insula. And, that it helps inhibit our automatic reactivity. That is the tendency to follow old patterns, such as catastrophizing. This certainly fits with peoples experience. Of course this is only a suggestion and the science is not really there yet regarding the interface between biochemical events in the brain and our experience.

Regarding your recent posts, my understanding is that there is really no evidence that distraction as a pain management strategy works, at least not to any meaningful way, but that being distracted by some thing you are interested in does. Also, that mindfulness practice is not a distraction mechanism, but rather a way to attend to the experience of pain, and thus divest it of some of those cognitive/emotional overlay that the physical sensations have acquired. Do you have any thoughts on this?

Hi Jim

Thanks for taking the time to comment on this, it’s great to have a practitioner of ACT and positive psychology becoming part of the dialogue. Yes, I think that mindfulness is an effective tool – and no I don’t think we have the technology to image this (yet) – and I still wonder whether there is a 1:1 relationship between what occurs in the brain and what we experience (the difference between knowing about and experiencing something – the qualia of something). Nevertheless, it’s an area to follow as we continue to explore what happens when humans attend to and perceive stimuli.

There is equivocal evidence with regard to distraction – I agree, what seems to be coming through the literature is that distraction from something is rather less successful (especially in terms of ‘rebound’ negative emotions) than attention to something that has other emotional qualities. For me personally, mindfulness is not about ‘distraction’ – asmuch as expanding my awareness of the wholeness of an experience (both negative and positive) so that the ‘judgement’ component is de-fused from the sensory component. In patients that seems to allow room for carrying out actions that enact what is valued in a person’s life, filling that person’s life with what is important (so they can focus on those things), rather than distracting from aversive experiences (which only seem to make those experiences more intrusive).

Attention management strategies can be a playful way to employ what the brain enjoys – novelty! and in so doing, add another tool in the repertoire for people who experience chronic pain.

I’m looking forward to hearing more from you!

cheers

Bronnie